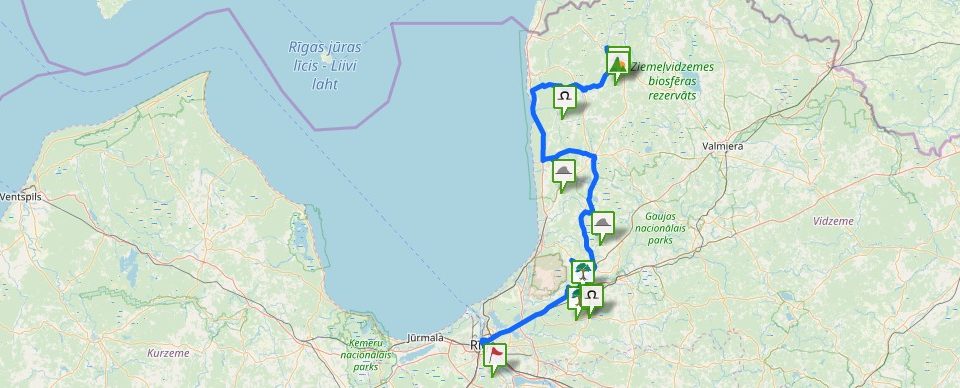

Near the Kuiķuli homestead on the bank of the Svētupe River, about 10 m high sandstone cliff outcrops. The cave is located in the upper part of the detrition, which is a little astray from the river bank. The first professional geologist, who described the formation process of Latvian caves, Professor of the University of Terbata Constantin von Grewingk believed that “the ancient Liv Sacrificial Cave” near the Kuiķuļi had been artificially formed (Grewingk, 1861: 21), nevertheless, this opinion is false, because the Liv Sacrificial Caves are ancient suffosive caves eroded in the sandstones of the Burtnieki series. The spring, which had formed the cave, ceased flowing over its floor already before 700 years, because there were coins of the 14th century found in the cave as offerings dug into approximately two meters deep layer of a landslide above the former level of the cave’s floor, where in former times the spring flew. The cave itself is falling to pieces – according to the drawing published by Friedrich Kruse in 1839, it, yet in 19th century, had one entrance. It is possible that the cave remained such till the beginning of the 20th century, if judged according to the cave description of that time: “When entering these caves, one finds himself in a large antechamber, from which there are smaller caves leading in three directions.” The ceilings of the wide “antechamber” having fallen down, two branches of the cave have remained, forming two separate caves nowadays. It is possible that in some place beneath the groundslid, the third cave’s branch, mentioned in the above cited text fragment, is hiding. It seems that this branch could be visited still several ten years after the “antechamber” had collapsed, because in a tale recorded in 1939 it is indicated that they used to call three caves by the Lielkuiķuļi as the Devil’s Caves. The largest branch of the Sacrificial Caves is 2-3 m wide at the entrance, deeper it becomes substantially narrower and lower. The length of this passage is 46 m, thus yet in the first half of the 70s – 80s of the 20th century this was considered to be the longest cave in Latvia. Accordingly, the length of the smallest cave is 19.5 m; at the entrance it is narrow and low, but inside its ceilings are almost 2 m high (Eniņš,1995h). In the cave’s ceilings, there are many so-called “Devil’s Chimneys”. Prior to the “antechamber’s” collapse, the total length of the Liv Sacrificial Caves was about 70 m (Eniņš, 1984a: 155). In summer 1971, G. Eniņš made first accurate measurements of the Liv Sacrificial Caves and drafted a plan of the remaining cave’s parts. In 1972 and 1973, investigation of the caves continued, because new specialists joined the expedition — a geologist Viktors Grāvītis and an archaeologist Juris Urtāns. Due to the fact that in 1972 attempts to dig off the 2 m deep sand hill, where the “antechamber” had collapsed, by using shovels did not succeed, a year later Viktors Grāvītis arranged a fire-pump, with the help of which there were tons of sand pumped into the Svētupe River, exposing, as a result, the floor level of the time when there were offerings made in the cave, thus providing an opportunity to perform archaeological excavation works in the cultural layer of the Sacrificial Caves led by Juris Urtāns. The work progress in the Liv Sacrificial Caves in 1971 –1973 was described in the press many times (Eniņš, 1972; 1984a: 146–155; 1995n V; 1998d: 58–59). The Liv Sacrificial Caves have played a distinguished role in research of Latvian cult and mythological caves: the most ancient written historic information sources about offering in caves are attributed right to these caves. On the caves’ walls, there is not only the most ancient currently known inscription carved on Latvian sandstones, but also many ancient signs, which, possibly, are as old or even older as the year numbers of the 17th century; moreover, for the first time scientists’ interest was drawn right to the ancient signs of the Liv Sacrificial Caves, thus discovering a completely new group of cultural and historic monuments not only in Latvia but also in the whole Baltic region – cliffs with signs. By examining the Liv Sacrificial Caves in 1971, Guntis Eniņš initiated a systematic examination of Latvian caves, applying for the first time later approved methods of cave examination; but in 1973 for the first time right in the Liv Sacrificial Caves, there were professional archaeological excavation works conducted in Latvian caves as such under the guidance of Juris Urtāns, during which there was a very rich archaeological material obtained (663 artefacts, out of which a part is coins and remains of various organic substances). According to information in literature, the Liv Sacrificial Caves were visited by a number of prominent people in 19th century. In 1822, a distinguished doctor and ethnographer Otto Hun found there sacrificed pieces of clothing and bread (Lövis, 1908). On August 15, 1839, during his visit to Latvia, when studying archaeological monuments, Professor of History of the University of Terbata Friedrich Kruse stopped there, discovering an offering of coloured wool and rooster feathers (Kruse, 1842: 7). The drawing made during F. Kruse’s visit and published later on is the oldest known drawing of the cave (ibid., Table 67, 3). A few years later, a painter from St. Petersburg August George Pecold, a member of the first Liv research expedition led by Anders Johan Sjögren, painted the Cliff of the Liv Sacrificial Cave. The entrance into the cave is not seen in the water-colour painting, which can be explained by the name of the painting “The Filled up Entrance to Svētciems”. Sjögren visited the cave on June 20, 1846, making the following entry in his diary: „… in the afternoon we had arrangements for an excursion, which we joined under the guidance of the master [proprietor of the Svētciems Manor House Carl von Fegesak]. Inland, on the bank of a small river, in the village of Ikskul, there was a place, which had been known for a long time as an ancient Liv offering place, thus all guests were accustomed to visit it. Namely, there was a cave in the steep sandstone wall of the high bank of the same river flowing to the sea called “Svietup” or, in other words, holy river. (..) In the upper part of the cave, a little bit astray, there is a fence named “Kujkul”. Here the old proprietor speaks also the Liv language,” (Blumberga, 2006: 22). There are relatively many thematically different tales and narrations recorded about the Liv Sacrificial Caves. The largest part of this material was recorded by schoolchildren of the Svētciems Elementary School during the 1939 folklore gathering campaign. 1) Just like about several other Vidzeme caves, in older times they also used to say about the Liv Sacrificial Caves that they are longer than in reality they are. In tales they mostly state that following a dog, which had been let into the cave with a bell tied to his neck, on the ground, the dog appeared out of the cave at the Burtnieki lake, more seldom — at Mazsalaca. If the tales were true, the Liv Sacrificial Caves would have been at least 42 kilometres long, because the Burtnieki lake is located approximately that far from the caves in straight line by air. Taking into account the current length of the largest entry into the Liv Sacrificial Caves — 46 m, then the exaggeration of the tales is 900 times! Mazsalaca is only a tiny bit closer to the Liv Sacrificial Caves. If in publications about these caves, there are any tales mentioned in relation to the caves, they usually represent that type of tales (for instance, Eniņš, 1972; 1984a: 147; 1998d: 58, etc.). 2) Tales related to Devil’s activities explain the most popular name of the Liv Sacrificial Caves in folkloric records — the Devil’s Caves. It is possible that in the image of the Sacrificial Caves’ Devil, the Livs have merged their notions about the nature (water) spirits and the Christian demonic Devil, because this folkloric layer differs from the Devil’s folklore characteristic to Vidzeme. It seems that this is a relatively new folkloric layer of the Liv Sacrificial Caves, which appeared later on when the cave lost its cult site function to a greater degree, i.e., around 18th –19th century. 3) Tales based on much older traditions narrate that there were offerings made in the Liv Sacrificial Caves. It is possible to link these folkloric texts with the archaeological artefacts obtained in the caves, which, basing on J. Urtāns research, are related to 14th–19th century. One should point it out there that the written records about visiting the caves dated 17th – 18th century, visitor’s observations of the 19th century, and archaeological artefacts provide much more detailed information than the folkloric material. Side by side with the discussed persistent folkloric motives in the introductory part and concluding part of the tales, one can occasionally find also other cultural and historic information. For example, one can find references to the fact that during the World War I, many people used the caves as a hiding place. This news has been proved also in literature (Lancmanis, 1924a III), at the same time in some other text it was emphasised, that “there are many names carved into the caves’ walls”. This news is absolutely true — on the walls of the Liv Sacrificial Caves, there are not only many names carved, there is also the oldest known dated inscription found, which in our times can be seen on the detritions of the Latvian sandstones, namely, the number of the year “1642” in the Little Sacrificial Cave. Two years later, some person named Matias Bach (must have been from Salacgrīva) left an interesting “double evidence” about himself by carving into the wall of the Great Sacrificial Cave an inscription “MATIAS : A : BACH AO 1664”, but in the Little Sacrificial Cave inscribing as “M : BACH SALIS AO 1664”. The first news about these old inscriptions was published by G. Eniņš and J. Urtāns, mentioning one or the other inscription in several publications. Due to this fact, G. Eniņš was criticised without any ground by some author, because only if one does not know that there are two different inscriptions by M. Bach of 1664 found in the caves, one can state that in the journal “Liesma”, when describing examination history of the cliffs and caves, the inscription “M:BACH SALIS Ao 1664” in the Liv Sacrificial Cave has transformed already into “+MATIAS A:BACH AO 1664”” (Stalidzāns, 1998: 25). In some Limbaži Tourist Guidebook it was stated that on the walls of the largest cave, one can find inscriptions dated back to 1617 (Limbaži, 1962: 37). It looks like this number of the year is no longer found nowadays. There are not only the oldest precisely dated inscriptions of all the Latvian caves and cliffs carved into the walls of the Liv Sacrificial Caves. On July 23, 1971, when making measurements of the Liv Sacrificial Caves, G. Eniņš found not only the old carvings by Matias Bach on the walls, but also different incomprehensible signs, out of which the most expressive ones were copied into his notepad and published later on (Eniņš, 1972: 27). This publication is significant for the study of Latvian signs on cliffs due to the fact that ancient signs had been mentioned and their approximate images published there for the first time. The same signs were studied and copied by J. Urtāns during the archaeological expedition; he was the first to describe the signs in scientific literature publishing also precise copies of several signs (Urtāns, 1975: 252-253; 1977: 91, 92). The studied signs have been described in more detail and illustrated in the publication devoted to the Liv Sacrificial Caves. Nowadays, the Liv Sacrificial Caves are a popular tourism object, which is well-known in Latvia, but in the oral traditions of the locals they have mainly become of secondary importance. For example, in some text recorded during a folkloric practice of the Liepāja Pedagogy Academy in 1996, one can clearly sense the literature sources, which have affected the narrator. Information about the cave as the ancient Liv Sacrificial Cave where offerings were made up till the middle of the 19th century, as well as a list of names of significant homesteads and places such as Pērkoni, Ūziņi, Svētupe and Svētciems have been taken over from J. Urtāns’ publications. There is another story related to the name of Lembit, the leader of the Estonian uprising, carved into the wall of the cave. After G. Eniņš had published in his articles six most impressive signs, which he had found on the walls of the Sacrificial Cave, an article by a local researcher Arturs Goba appeared with the title “Could our ancestors write?”, which was later re-published in the book of the same author (Goba, 1989; 1995: 133–136). In this article, the author criticizes J. Urtāns commentaries about the signs of the Sacrificial Cave, thus supporting rather the hypothesis of Galgauska’s local researcher Oļģerts Miezītis, stating that these were runic signs denoting, if read in reverse, the name of the Estonian uprising leader Lembit. Nonetheless, such an interpretation is impossible even theoretically, because the signs in the cave had not been carved in a regular row just the way they were published, which was pointed out later also by G. Eniņš (1998d: 58). Still it was enough with the intriguing article by A. Goba for this information to remain in the people’s memory. The concluding part of some other tale is very interesting, which could be considered as a modern belief: „There is an opinion that there are people who still make unconsciously offerings to the gods, because many have lost some belongings in the cave, for instance, a ring, money, etc.” It seems that even nowadays for a small part of the society the Liv Sacrificial Caves have preserved the status of sacredness. For example, in 2008 during the summer solstice festival in the antechamber, there was a huge pile of bonfire ash smoking, but in several other places of the cave, there were bunches of flowers, eatables and chaplets left apparently as offerings. Since 1967, the Liv Sacrificial Caves are an archaeological monument, but since 1977 – a protected geological object, thus bonfires and inscriptions into the walls of the cave are regarded as devastation of an object under protection, thus it is a criminal act. The cave has filled up for about 2-3 meters in comparison to the floor level exposed during the expedition of 1973. It seems that the signs on the wall of the cave’s antechamber have disappeared. There are also new signs carved into the walls. In several cavities of the main cave’s wall, there were wildflowers places yet in 2011. (Literature: Kruse, Kruse, 1842: 7; Grewingk, 1861: 19, 21; Protokoll 1869: 181; –ru –rs 1892; Richter 1909: 381; Kurtz, 1924 Nr. A108); Lancmanis, 1924a III (Valmieras apriis, Nr. 4); Cukurs, 1930: 47, 56; Bregžis, 1931: 11, 44, 88; Vanags, 1937a: 117; Priednieks, 1967: 89 (Nr.122); Eniņš, 1972; 1984a: 146–155; 1992c: 69; 1993c I: 10–12; 1995h; 1995n V; 1998d: 58–59; Urtāns, 1973; 1975; 1977a (Nr.10); 1980; 1997: 93-98; 2000; Balaško, Cimermanis, 2003: 207; Laime, 2004b: 47, 62. After: S. Laime. Holy Underground. Folklore of Latvian Caves. (Svētā pazeme. Latvijas alu folklora.) – Rīga, Zinātne, 2009., with J. Urtāns addendum)

It is a good example of how, probably, to combine tourist interests and those of proprietors. Nevertheless, many petroglyphs have been harmed and even disappeared.